Dr Sharon’s Blog

Welcome to the contents of my Researchology head

Sunday 8th September

This blog is all about the lessons that I have learned as they can be applied to research. Some of them have been learned in educational research, some in my experience as an educator or a student; others have been learned in life, and applied to research. When I was a little girl, my gran always used so say “Learn from other people’s mistakes my girl. You don’t need to make them all yourself.”

So, for what it’s worth, this section contains my ad hoc thoughts and experiences as you might apply them to your own research, workplace or life in general. If there’s something in here that helps just one person, then it’s worthwhile. And if it doesn’t help you, it might at least make you smile!

Tuesday 10th September

Who doesn’t love a hotel “freebie”. I use the word “freebie” advisedly, because if you have paid your room rate, it’s not free. You’ve paid for it, so you’re entitled to maximise its utility, right? The important thing about maximising the utility of any resource, is to reflect on its value to you, before you commit yourself to using it in your research, and potentially allowing it to shape some of your decisions down the line.

In all honesty, I can’t remember which hotel the toiletries in the photo above came from. It’s not really relevant. What was relevant to my decision to take them home was that I always like to have a few miniature toiletries for travelling. Specifically for when I’m going to stay in a “new-to-me” location for the first time and am not quite sure what I might expect to find. Early August presented me with one such occurrence, so I scooped the bottles from the bathroom shelf into my bag, and off I went.

Taking my first shower on arrival at my destination, I discovered that it was ridiculously difficult to get the contents out of the bottles; so their value to me was, therefore, zero. If you look closely at the photo you can see that the bottles are now slightly misshapen because I really did my level best so squeeze out of them what I needed. Had I taken the time to check the bottles out before I stuffed them into my bag, I would have discovered that before I left home; and taken something else. It never occurred to me that the resources that looked fine at first glance would useless.

So what does this have to do with research? Well, it can apply on many levels. You’ll get lots of advice from different people in different capacities as you design and carry out your research. It’s important, though, to remember that it’s advice rather than direction. People will point you to things that have worked for them. This could be literature, theories on which to base a theoretical framework, data collection methods and instruments, coding frameworks – the possibilities are almost endless. Just because it worked for them, doesn’t automatically mean that it will work for you. That decision is yours. So for each decision you make on your research journey, ask yourself why you are making the decision you’re making. If you can’t provide yourself with a rationale for your decision, ask yourself whether you should be taking it. Discuss this with your supervisory team, and anyone else whose opinion you respect.

At every stage in your research journey, you need to be clear about the decision you take, and the resources that you use. Get used to being proactive in your decision-making. It’s a habit that you need to make the effort to form, but it will stand you in good stead, as your journey progresses. Get into the habit of recording your decisions, so that you can explain them in your writing. It’s much easier to remind yourself from your records than it is to trawl your memory for your train of thought. And if you are asked any “why” questions in your viva, you’ll know exactly what the answer is.

Tuesday 17th September

Reach For The Stars

When you are a postgraduate student, there are two scenarios that can dominate your horizons. One is the here and now, the vicissitudes of life, the juggling, and getting to the end of the week/ the next deadline. A PGCE PCET student of mine, a Commander in the Royal Navy used to describe their present challenges as the “crocodiles closest to my canoe”. The other is your endgame, as in your final deliverable, be that submission of a Masters dissertation or a doctoral viva. Sometimes, though, we are so busy planning and creating contingencies for a variety of worst-case scenarios that we forget to create headspace for the best possible scenarios.

The fabulous Dr Rowena Senior conducted a succinct but really powerful workshop last week at the International Creative Research Methods Conference 2024 about story creation for professional development and using future stories to focus on your ambition. So, my challenge to you this week, is to adapt Rowena’s presentation to focus on your own academic ambitions when your current postgraduate research is finished.

First of all, try to think about what that ambition is. What have you learned from your studies so far. What have you learned? What do you want to achieve? Are you happy to leave your dissertation/ thesis on the shelf, or do you want to do something with it? If so, what? Who needs to read your research? How are you going to make that happen? If you don’t currently have any goals that you want to realise when your endgame is completed, or objectives that you want to achieve, try to formulate some. Then use the outputs from this thinking to construct the narrative of a story about your best possible academic self. To do this, think about your academic and professional life in the future. Imaging that everything to do with your endgame has gone as well as it possibly could have done. This could be that you’ve achieved a distinction in your Masters dissertation, that you’ve successfully defended you doctoral thesis and have only five minor amendments to make that will take you less than two weeks.

Rowena then says that you should write about what you imagined for between 10-15 minutes. As discussed above there’s a temptation to focus on overcoming barriers, because that’s what we do as practitioners and postgraduate students (especially if you’re part-time and are juggling different priorities that look set to collide). Don’t worry about how it looks, your story is for you at this stage. Also remember to look as far beyond your endgame as you can. Look beyond surviving to thriving. For example, when I was a doctoral student; my goals were to survive my viva with amendments of any sort rather than a resubmission, and to visualise myself walking across the stage at graduation with the University’s then Vice Chancellor placing the floppy hat on my head. For the record, I survived the viva with minor amendments, and second didn’t quite pan out because of covid. Graduation was delayed by 15 months because of lockdowns, and when we got there in November 2021, restrictions on physical contact meant that you had to put your own hat on your own head, and simply doff it at the VC. But the key point is that I restricted myself to the endgame, and the immediate aftermath thereof, rather than focusing on my own forward trajectory.

Rowena advises that you should then think about who in your academic or professional life you should share your ambition with. Who can help you achieve it? Can you apply this approach to any other ambitions that you have for any other areas of your life?

The theoretical underpinnings for this workshop come from the Best Possible Self intervention (BPS), which was developed by King (2001)

‘…the “Best Possible Self” (BPS) intervention, which consists of writing about one’s best possible self in the future after everything has gone as well as it possibly could.’ (Carrillo et al 2019, p. 2)

Our stories (in whatever context we consider them – academic or otherwise) are important because they ‘…represent our unique experiences, lessons learned, and wisdom gained…’ (Box and Mocine-McQueen, 2019, p. 8). And for every one of us, our postgraduate journeys are different. There will be some commonalities in our learning and experience, but there will also be aspects that are unique to our particular contexts and circumstances.

Have a go at this and think about how it was for you.

Loveday at al. (2018) tell us that BPS can boost health and wellbeing.

Rowena also advocates that it can also increase optimism ad positive

affect. For me, the experience of writing the BPS intervention was

surprisingly difficult at first, because (as previously discussed) it’s almost a

reflex to dismantle the barriers to achievement rather than project forwards.

If we’re focussed on finding the answers to the negative “what if” questions,

we might never get as far as our BPS. To

envisage a BPS was both empowering and affirming. Give it a go and let me know how you get on.

References

-

- Carrillo, A., Rubio-Aparicio, M., Molinari, G., Enrique, Á., Sánchez-Meca, J., & Baños, R. M. (2019). Effects of the Best Possible Self intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloSone, 14(9), e0222386. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222386

-

-

- Box, H. and Mocine-McQueen, J. 2019. How your story sets you free. San Francisco: Chronical books.

-

- King, L. A. (2001). The health benefits of writing about life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27(7), 798–807. doi:10.1177/0146167201277003

-

- Loveday, P.M., Lovell, G.P. & Jones, C.M. The Best Possible Selves Intervention: A Review of the Literature to Evaluate Efficacy and Guide Future Research. J Happiness Stud 19, 607–628 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9824-z

-

- Senior, R. (2024) Story creation for professional development: using future stories to focus on your ambitions International Creative Research Methods Conference, 9th September, Manchester

Tuesday 24th September

How many “I”s are there in academic writing

The short answer in educational research is three, whether you answer the question literally, or philosophically. Literally, there is one I in academic and two in writing. Philosophically, there are also three These are the discursive “I”, the methodological “I” and the knowledge making “I” (Giltrow et al. 2009) (see below).

As an EdD candidate, researching my own students on the course that I led, in the institution where I worked, I was adamant that my thesis needed to be written in the third person for transparency and authenticity. My supervisors were less convinced than me that this was a good idea, and it was suggested that I might reconsider my decision. I did reconsider my decision and decided that it really did need to be in the first person. Given that there was disagreement with my supervisors on this point, I decided that the best way to deal with this was to include a justification for the use of the first person in the introduction of my thesis so that readers and examiners alike were clear that I had taken a deliberate decision, and why I had taken it.

There are both general and topic-specific takeaways from this post. The general takeaway is that as a postgraduate researcher, you need to take ownership of and be able to defend all every single decision that you take (or have taken) in relation to your research, in case you are asked to do so in your viva or presentation. If you are asked why you did something, replying “because my supervisors told me to” is not an acceptable answer! The topic-specific takeaway is that those who have presented their own research in a particular way (in this case in the third person) may find that convention difficult to let go of. You need to do what’s right for your research; and make sure that you have appropriate authority to justify your position. My justification below, is adapted from my thesis. I’m not offering this as an exhaustive explanation, but rather as a starting point from which to develop your own justification.

The Traditional Approach

The traditional view from a science-based perspective is that there is no place in academic writing for the use of the first person (Chalmers, 1982). Webb (1992) agrees that objectivity is traditionally represented in academic writing by the use of the third person. More recently, Robson and McCartan (2016) tell us that traditional academic writing has been in the past tense, and that passive voice is an attempt to demonstrate the credentials of the documented research activity. They argue that excessive use of the authorial “I” suggests author bias and / or naivety.

Alternative Perspectives

Haraway (1988) tells us that writing in the third person constitutes a “god trick” in which a researcher appears both ubiquitous in and absent from their research. Thomson and Kamler (2016) argue that the first person is a valid form of academic writing, and argue a researcher should situate themselves specifically within their text to make themselves visible within their work. This echoes Jones’ (1992) view that the use of the first person provides author voice and visibility in research. Ivanic (1998), contends that the use of the third person abdicates responsibility for one’s work; whereas the use of the first person constitutes acknowledgement of responsibility for claims made in relation to, and resulting from, research. From the perspective of clarity of writing (and therefore reader accessibility), Day and Gastel (2017) posit that writing in the first person helps authors to articulate actions taken and conclusions drawn in a direct and concise style.

Ivanic’s Continuum

Ivanic (1998) presents a range of what she describes as alternative ideologies of knowledge making in Higher Education. One such ideology is represented by her objectivity/subjectivity continuum in relation to the use of the first person in academic writing as she contends that the use of the first person in academic writing is neither binary nor straightforward.

|

|

|

Subjectivity |

|

|

Not using ‘I’ at all |

Using I as the personal pronoun for verbs associated with way that the writing will be structured but continuing to present content as factual and/or objective. |

Using I for verbs in relation to the research process, for example aligning oneself with a particular stance |

Using I for verbs associated with cognitive acts such as knowledge claims, and positioning contribution to a field. |

|

“I” is absent |

“I” is voiceover

|

“I” is researcher

|

“I “ as contributor to knowledge and field

|

Table1.1: The objectivity/subjectivity continuum: adapted from Ivanic (1998)

How many Is did you say there were in academic writing?

Giltrow et al. (2009) present three different iterations of the first-person singular in academic writing. These are the discursive “I”, the methodological “I” and the knowledge making “I”. The discursive “I” usually writes about discourse action in their capacity as a researcher (e.g. “I explore”). They highlight what they refer to as “forecasting” (2009:200) as a particular activity of the discursive “I”, in which the writer signposts for the benefit of their reader how their writing will be organised.

According to Giltrow et al. (2009), the methodological “I” appears where a researcher is personally present as an agent in their account of their methodology section. Such use of the first person is associated with the decisions and actions taken in pursuit of data collection. In relation to qualitative research, Giltrow et al. (2009) highlight a type of methodological “I” who places emphasis on their own role in relation to knowledge creation within their methodological account in order to illustrate the full perspective from which they have undertaken their work. For example, you might communicate something like feminist reasoning overtly within your writing in order to make sure that your reader understands that the knowledge that would be created by you would be relative to the subject position that you inhabit.

The knowledge-making “I” is positioned by Giltrow et al. (2009) as someone who clearly identifies their own role in relation to knowledge creation. This is similar to the methodological “I” described above, but it is different because it focuses on the knowledge created rather than any ontological or epistemological position inhabited in relation to the methodological decisions and actions that were taken. They suggest that the “knowledge-making I” can either highlight a departure from established knowledge or suggest an indication of the limitations of the knowledge created. So, if you are carrying out single institution research for which generalisability is neither sought not claimed.

There are other methodological arguments for the use of the first person in academic writing. Webb (1992) suggests both methodological decisions and data analysis choices are manifestations of personal decisions taken by researchers. You could develop this further to argue that the personal decisions permeate all areas of postgraduate research in education. You select your literature, and your theoretical perspectives. You formulate your recommendations and claim your contributions to knowledge. Webb claims that whilst writing in the third person has been traditionally viewed as an indicator of objectivity, it is really deception because the author is obliterated as an “active agent in the construction of knowledge” (1992:749). Webb’s (1992) observation reinforces Smith’s (1987) argument that anonymity and detachments can extinguish, or at least mitigate, contextual factors. This perspective is developed by Agaolue (2013:np), who invites us to consider the potential loss of contextual information when the passive voice is used to describe a scientific laboratory process:

“Consider a sentence like “slides were carbon-coated for EMP analysis”. By whom? By me?? a cack-handed undergraduate summer student? By a technician with 30 years’ experience? These things make a difference. In a lot of cases, you remove information when you recast a sentence in the passive.”

Methodological Considerations

The methodological arguments deal with four distinct areas: ontology and epistemology, reflexivity and credibility. From an ontological perspective, Ivanic (1998) suggests that the first person is required where a researcher claims a constructivist ontology in which reality may be local, contingent or socially constructed.

Dean (2015) asserts that reflexive practitioners must acknowledge the presence of themselves in their work and part of the application of their own rigorous standards to their own work. This develops Ivanic’s (1998) argument that the use of the third person fails to acknowledge the researcher and their role in writing, and reinforces Punch and Oancea’s (2014) assertion that there is no such thing as positionless research.

The development of vocational and professional courses in HE has led to an increased requirement for reflexivity in terms of reflecting on methodological decisions, and courses of practical action. Moberg (2013) suggests that writing in the first person acknowledges the perspectives of a researcher which provide their reader with transparency in terms of the potential biases to which an author may subjected, and the extent to which an author has addressed those biases. Similarly, Mascia-Lees and Black (2017) point out that a reflexive writer will acknowledge the role that they play in their research, and the potential impact that this might have on their participants. Whilst it’s fair to say that both Moberg (2013) and Mascia-Lees and Black were commenting from an anthropological perspective, writing yourself you’re your research is not the exclusive domain of anthropology. It can be extended to educational research, particularly from the perspective of own institution research, where your research often relates to and arises from your own professional practice.

Webb (1992) contends that alternative criteria to validity and reliability are required for qualitative research. For example, Lincoln and Guba (1985) suggest credibility as an alternative criterion for internal validity in evaluating qualitative research. Auditability is a key aspect of credibility, and they indicate auditability is both present and apparent when a reader can clearly follow the decision trails used by the researcher. It can be argued that the transparency provided by writing in the first person facilitates auditability, because it very clearly locates the researcher in their research and identifies them as what Guba and Lincoln (1981) would call a subject in their own studies. Furthermore, the American Psychological Association advocates the use of the active voice of the first person (Lee, 2014).

References

AGAOGLU, A. (2013) ‘Academic writing: why no ‘me’ in PhD?’ at <https://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2013/apr/19/academic-writing-first-person-singular> accessed 28/09/2017.

CHALMERS, A.F. (1982) What is this thing called Science? Milton Keynes: Open University Press

DAY, R. & GASTEL, B. (2012) How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper, Seventh Edition,

Cambridge University Press.

DEAN, J. (2017) Doing Reflexivity: An introduction. Bristol: Policy Press

GILTROW, J. (1995) Academic Writing. Writing and reading across the disciplines. Ontario: Broadview Press

HARAWAY, D. (1998) Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege

of partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14(3) 575-99

IVANIC, R. (1998) Writing and Identity: The discoursal construction of identity in

academic writing. Netherlands: John Benjamins B.V.

JONES, A. (1992) Writing feminist educational research: am “I” in the text? In S. Middleton and A. Jones (eds), Women and education in Aoteroa (pp18-32, 224) Wellington: Bridget Williams Books

LINCOLN Y.S. AND GUBA E.G. (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry. California: Sage

Marcus, G. E. (2015) ‘Reflexivity in Anthropology’ in International Encyclopaedia of the Social

& Behavioural Sciences (Second Edition), Volume 1, pp. 88-92.

Mascia-Lees, F. E. & Black, N. (2017) Gender and Anthropology, Second Edition, Long Grove:

Waveland Press.

MELLORS-BOURNE, R., ROBINSON, C., AND METCALFE, J. (2016). Provision of professional

doctorates in English Higher Education institutions. London: HEFCE

Metcalf, P. (2016) Anthropology: The Basics, Taylor & Francis e-Library: Routledge.

Moberg, M. (2013) Engaging Anthropological Theory: A Social and Political History, London:

Routledge.

PUNCH, K. AND OANCEA, A. (2014) Introduction to Research Methods in Education (2nd

Edition). London: Sage

QUALITY ASSURANCE AUTHORITY (QAA) (2015) Characteristics Statement: Doctoral Degree. Gloucester: QAA

ROBSON, C. AND MCCARTAN, K. (2016) Real World Research: A resource for users of social

research methods in Applied Settings. Chichester: Wiley

SMITH, D. (1987) The Everyday World as Problematic. A feminist sociology. Milton Keynes: Open University Press

THOMSON, P and KAMLER, B. (2016) Detox your writing: Strategies for Doctoral Researchers. Abingdon: Routledge

WEBB, C. (1992) The Use of the first person in academic writing: objectivity, language and gatekeeping. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1992, 17, 747-752

Friday 1st November

Do Sweat the Small Stuff

As a self-confessed control freak, I have spent much of my

adult life learning not to sweat the small stuff and using my own rag-rated

version of the Eisenhower matrix to prioritise my time.

The RAG-rated Eisenhower Matrix

|

Do it myself, ASAP.

|

|

|

Important and not Urgent |

Allocate time to do it myself.

|

|

Not important but Urgent |

Delegate it/ pass it to someone else.

|

|

Not important and not Urgent (but possibly interesting) |

Delete it |

As a busy parent with an often-absent-with-work spouse,

young children, elderly parents and in-laws and a FT job, I spent quite a lot

of the time that I was on my research journeys combining the proactive

organisation of my studies with reacting to the vicissitudes of my personal and

professional life that the foregoing combination bought with it. My mindset always used to be that I needed a

significant tranche of time to make any progress with my studies, and that it

wasn’t possible to make any meaningful progress in blocks of time any less than

two hours. And because that’s what I believed, that’s how it was – because for

a long time, I didn’t challenge that assumption. It was my assumption, based on

my experience – so why would I challenge it? So when something happened (accident/illness

of a family member, for example), I’d mourn my lost study time, and sometimes

end up behind my planned curve.

As my job began to focus exclusively on working with

Postgraduate students, some of whom were part-time, I began to hear many

reasons for delay in deliverables from students that echoed my own, and some of

those reasons related to inability to change previous study practices because

“the way I’ve always done it works the best for me”. I had on PGCE PCET student, who was a

Commander in the Royal navy, who would always explain his delays in terms of

having to deal with the “crocodiles closest to his canoe”. So, the RAG-rated Eisenhower matrix morphed into

the RAG-rated crocodiles closest to my canoe.

RAG-rated Crocodiles Closest to my canoe.

|

Is |

Attend to it myself, ASAP

|

|

Is someone in need but not distress |

Allocate enough time to work with them to kick it into the long grass.

|

|

What will get me a P45 if I don’t do it this week? |

Allocate enough time to do enough to make it SEP.

|

|

Not important and not Urgent (but possibly interesting) |

Make a conscious decision not to get side-tracked, and delete it |

Key

|

SEP |

Someone |

|

Delete |

Wash that |

I would often counsel students to try to look at things

through a slightly different lens=making minor changes rather than major ones

(e.g. go to every other home football match rather than not go at all). As

making use of small chunks of time seemed to be as much of a problem for me as

it was for my own students, I decided that this was something that I needed to

work on. So instead of making the statement “I can’t do anything with a spare

half an hour”, I began to ask myself the question “What can I do in half an

hour?”. And the answer was, as it

happened, quite a lot. Some of the things that I leaned that I COULD do in half

an hour are set our below.

·

Check six references. Where I use a number, the

number is arbitrary, and I know that it will vary depending on the complexity

involved in each case. But you know what I’m saying here. Spend your half hour

checking references. If you only manage one reference, that’s a result. If you

manage more than one, you’ve smashed it!

·

Proofread (a number of) small sections of text.

·

Make a note of some personal reflections on what

you are working on at the moment (e.g., what went well in a particular tranche

of data collection? What learning can I take from it? Were there any issues? How

am I going to address them).

·

Read (part of) a journal article. This might

require some forethought, depending on your reading preferences. I have never

been a great screen reader, and I’m much happier with a paper copy and a

highlighter in my hand, so I always had to make sure that I had a journal

article and a highlighter in my bag at all times. If you’re a screen reader,

your forward planning might be downloading articles or checking that there will

be adequate wi-fi where you think that you are going.

·

Address at least one item of feedback on a piece

of draft writing. This is another tip that is “elastic”, because exactly how

much you can get done in a short space of time will depend on the complexity of

the feedback.

·

Re-visit/ review your time plan for the rest of

the month.

This isn’t – and isn’t intended to be an exhaustive list. At

the moment, you’ll just have to take my word for it that the more I discovered

the art of the possible, the more things that I could usefully do in a short

space of time. My learning was simply this – by looking at small units of time

through a slightly different lens, my mind was opened up to possibilities that

I simply hadn’t acknowledged before, because I had closed my mind to things

that weren’t congruent with my existing modus operandi. I knew that things

would have to be different whilst doing a doctorate alongside life and a FT job

as a senior lecturer, but sometimes it was easier to stay in my comfort zone

and find reasons (excuses) for what I hadn’t done rather than stepping out of my

comfort zone, taking the plunge, and just having a go. When I stopped making excuses, and just had a

go, it wasn’t half as challenging as I had previously made up my mind that it

was going to be.

Monday 4th November

Tell the Truth, and call out the Instant Gratification Monkey

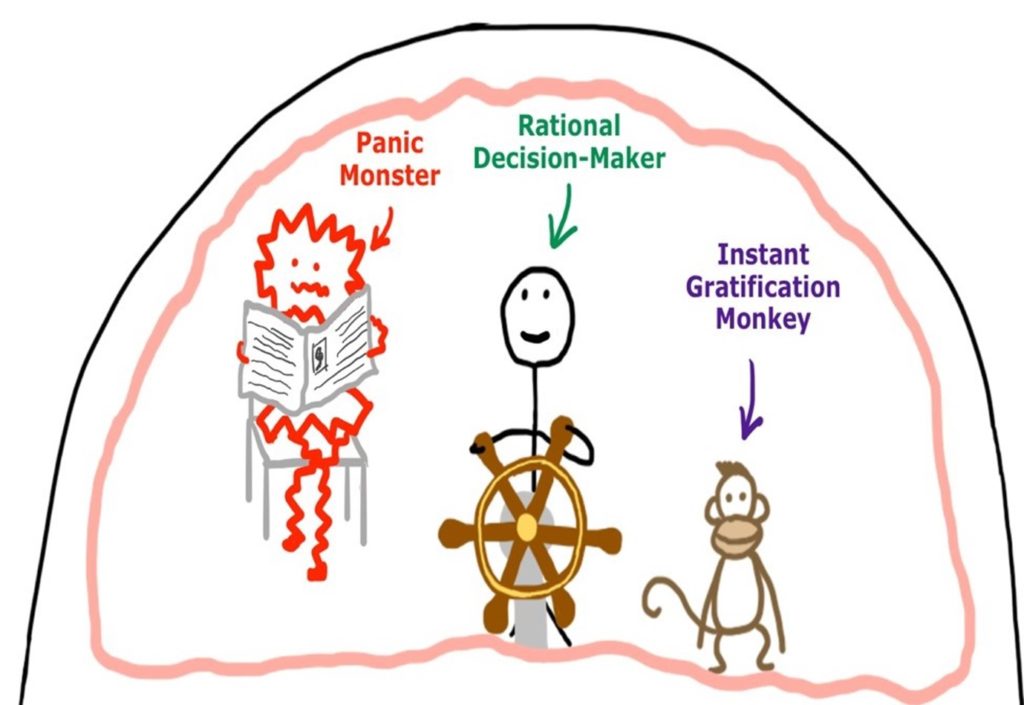

The Rational Decision maker, the Instant Gratification Monkey and the Panic Monster are all the brain children of Tim Urban, introduced in his TED Talk on procrastination in 2016. Before you do anything else, you need to watch this TED Talk, which you can find here Tim Urban: Inside the mind of a master procrastinator | TED Talk

In a nutshell, the Rational Decision-Maker (RD) represents us as postgraduate students, steering the ship of our research. We have a timetable, and we know what needs to be done and by when. The Instant Gratification Monkey (IGM) is a creature who lives only in the present moment, and has two drivers, things that are “easy” and “fun”. In Urban’s TED talk, the IGM distracts the RD from the tasks in hand with trivia. The Panic Monster (PM) is the only thing that the IGM is afraid of, and when time is very short, the PM appears, frightens the IGM away, and the RD is left to pick up the pieces to deliver their work on time.

In the realms of the real world of part time postgraduate study the IGM is a master of disguise and replaces trivia with real-time issues. It will hi-jack you with what it represents as truths rather than trivia and do its Svengali-like best to convince you that you are allowing yourself to be side-tracked by the Greater Good. Our challenge is to call out the IGM, and to unpick whether or not the distraction is as important as it seems.

The hard part is that there will always be genuine emergencies where things are important and urgent and can only be done by you. Sometimes, the IGM really will be telling you the truth. In 2015, I was finalising the first draft of my literature review when I got a call to say that my dad has suffered a stroke, which would end his life 4 days later. As I ran out of the house to my car, I was shouting instructions to my husband to email it (in its incomplete state) to my supervisor with an apology, in order to meet my deadline). On this occasion, the IGM was right. It was a real emergency, it was important and urgent, I did need to go myself and I needed to go immediately.

The following year, the IGM persuaded me that it would be a good idea to make myself available to MA students for tutorials 3 evenings a week instead of 2; because it was in the best interests of my students to have a greater choice of timeslots. As it involved my day job and the needs of my students, I was comfortable in not challenging the IGM’s line of reasoning. It was also easier for me personally to tie up my time in the important and worthy aim of supporting my students than it was for me to address the challenge that had arisen in my research when I realised that my data didn’t fit my preferred theoretical framework.

The reason why the IGM is so dangerous is because it uses legitimate considerations such as meeting the needs of others, and to achieve a work-life balance to obfuscate your commitment to study and your time allocation. The IGM is insidious because it will encourage you to legitimise your procrastination. It will substitute Urban’s “easy” and “fun” for supporting the Greater Good or servicing the requirements of your day job. So, re-engage with your time allocation. Remind yourself of how you got to allocating your study slots in the first place. Whip out your version of your Eisenhower matrix and revisit the crocodiles closest to your canoe (if this makes no sense to you, refresh your memory by revisiting the Reach for the Stars blogpost). Tell the IGM that you have the measure of it and challenge it to provide you with evidence that the procrastination that it is proposing is really anything other than procrastination.

I can’t guarantee that this will ensure that the IGM exists screaming as it does in Urban’s TED-talk graphic, but I do find that if you keep asking it the “why” question (e.g. Why will it be better for the students to have a choice of three nights a week instead of 2? -and then ask the why question again), it will give up and slink off into the distance, leaving you to answer your own questions and make your own mind up about the Greater Good.

If you need an ear to talk this through, please get in touch through the website or the Educational Researchology Facebook page.

References

Urban, T. (2016). Inside the mind of a master procrastinator [Video file]. Web. (Accessed 3rd November 2024)

Good luck to the team at the ICRM Conference tomorrow